Bullfighting and Modern Spain

(Text: 2008; Photos 2003)

“La corrida es una mierda,” Jose sneers. “The bullfight only is for the fascistas. You should not go. They slaughter the toros for nothing but national pride. Who can be so proud of murder but a fascista?”

“Well, I already have a ticket, and I want to see it for myself,” I respond.

And so began my lessons in Spanish culture, a culture as varied and full of contradictions as any other.

At home with my host family, in an apartment on Camino de Ronda in Granada, I watch shaky home videos of ten-year-old Juanma practicing torero moves on a young cow. His father Manuel—a large man who laughs loudly and works at a bank hours north of Granada—watches with a proud gleam in his eye. When my roommate and I first arrived from the United States, all we could understand was his hand gesture of a plane in the air while pointing at us, as if to say “you’ve come a long way, eh?” After being here for a month or so, we now understand as he tells us in Spanish that his son takes weekly bullfighting lessons and one day will make his father very proud. In households like that of my host family, tradition still runs deep.

Many of the younger generation of Spaniards I’ve met don’t share this enthusiasm for tradition. In fact, most of my Spanish friends despise bullfighting, the same way they despise the nationalist symbol of the Spanish flag and the strict Catholic morals left over from the Franco regime. They are anarchists at heart, and extremely aware of the dangers involved in giving too much power to one person. Better to govern yourself than trust someone else to do it.

During Franco’s regime, bullfighting was supported by the state and held up as an important tradition and national symbol of Spain. Franco often used these events as tools to showcase his own power and political agendas. Because of this, bullfighting, along with many other national symbols, came to be associated with the authoritarian regime.

During that time, all variations from Franco’s chosen “norm” were prohibited. The individual, like the bull, was sacrificed for the good of Franco’s Spain. All regional languages, like Basque and Catalan, were banned. All regional flags were burned in favor of the united Spain, under one, all-encompassing flag. And no deviations from the heterosexual were tolerated. Those who chose to ignore these rules were killed or simply disappeared. Now many Spaniards have come to equate patriotism and traditionalism with fascism, which is why you will not see many Spanish flags flying when you visit Spain—not like in the United States, where there is rarely a time that a flag is not in sight.

Keep all of this in mind as you watch the films of Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar. The flesh, the sexual deviancy, the freedoms and repressions the characters wield like war paint—this is post–Franco Spain.

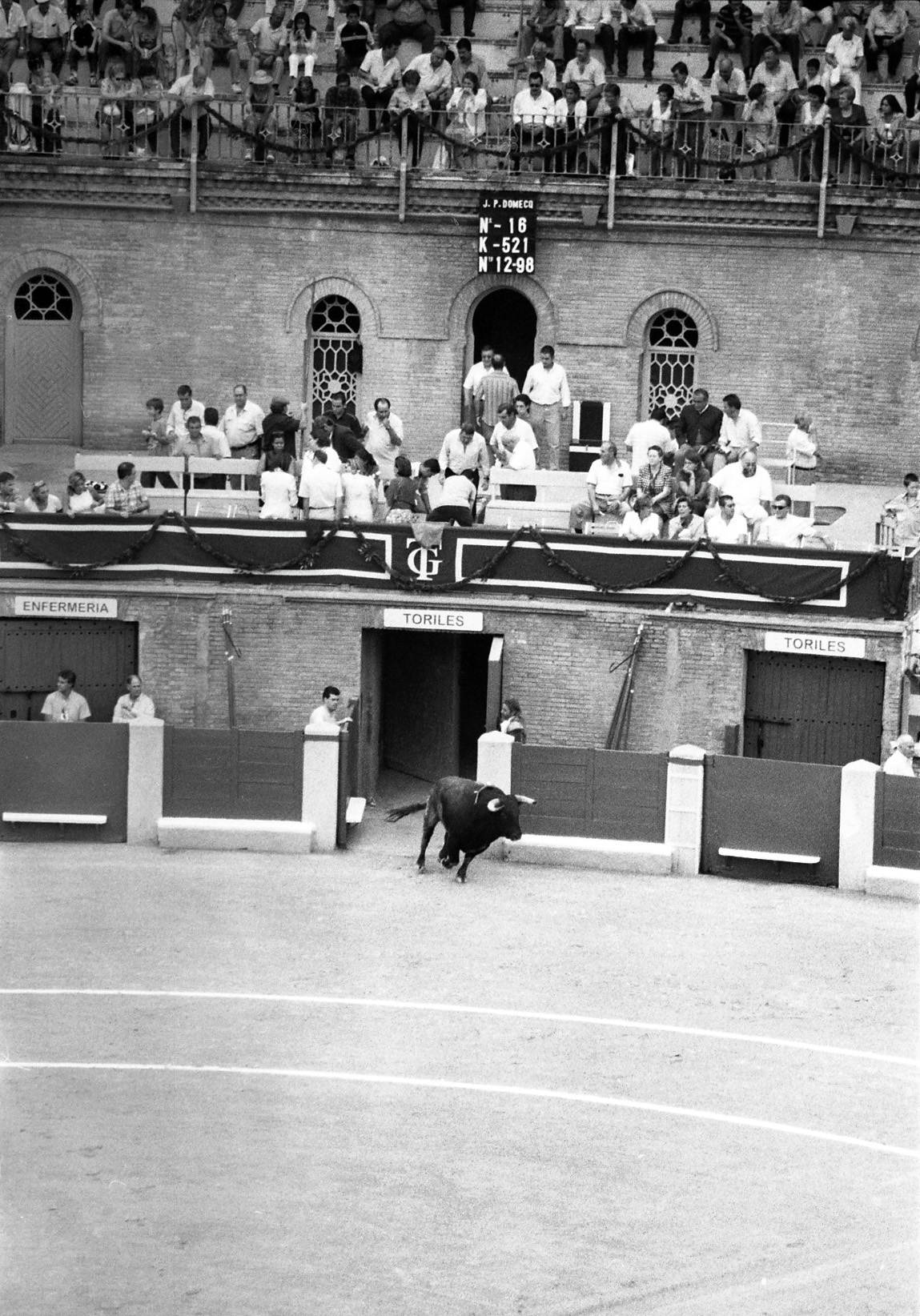

I’m sitting with two other American students in the Plaza de Toros in Granada, a hot Spanish sun beating down on me and a heavy telephoto lens in my hand. It feels good finally to sit, after battling our way through crowds of Spaniards outside the arena, all straining to get close to the well-known toreros for an autograph. I know nothing about what I’m going to witness today, but I’ve grown used to that feeling, being in a foreign country for so many months.

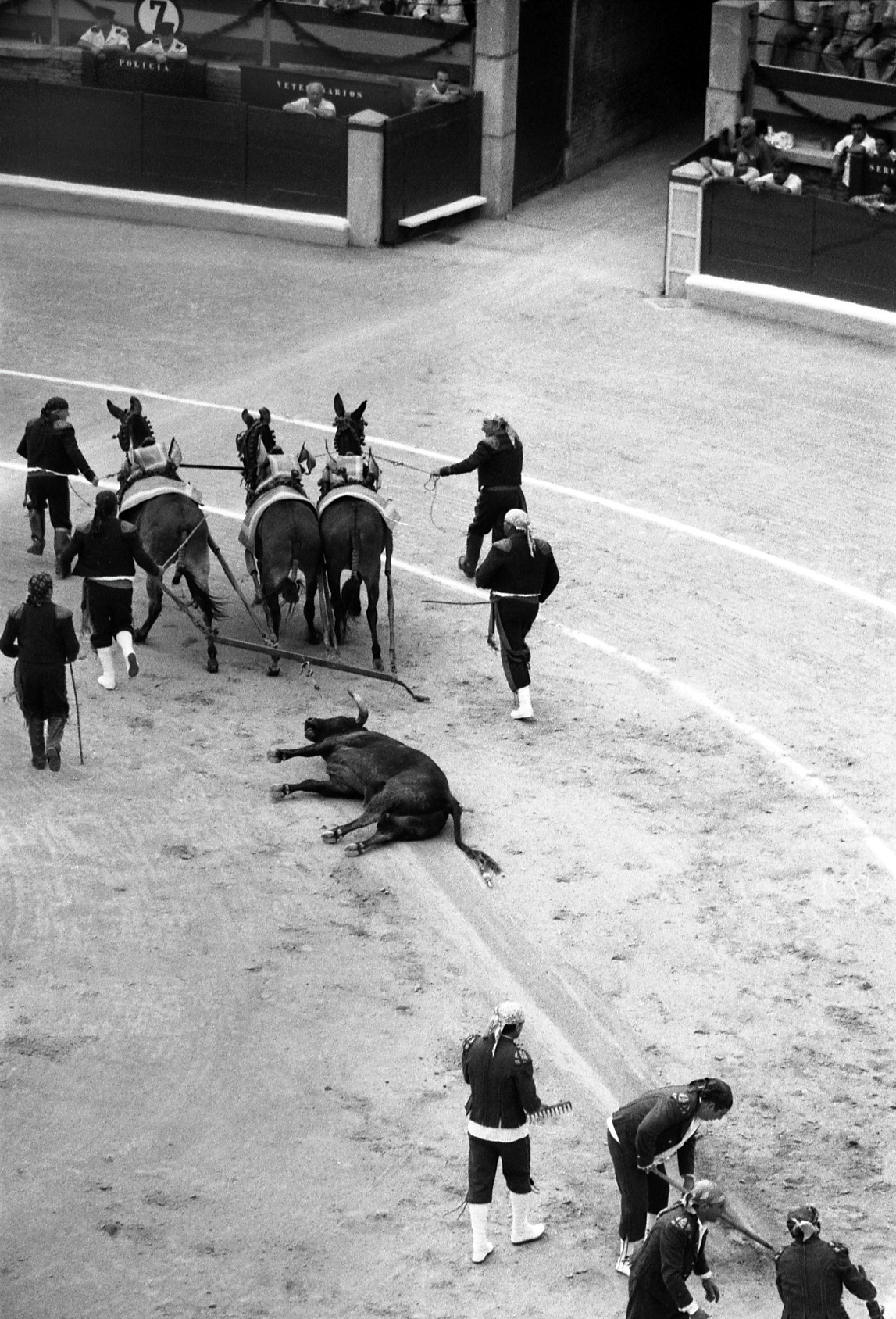

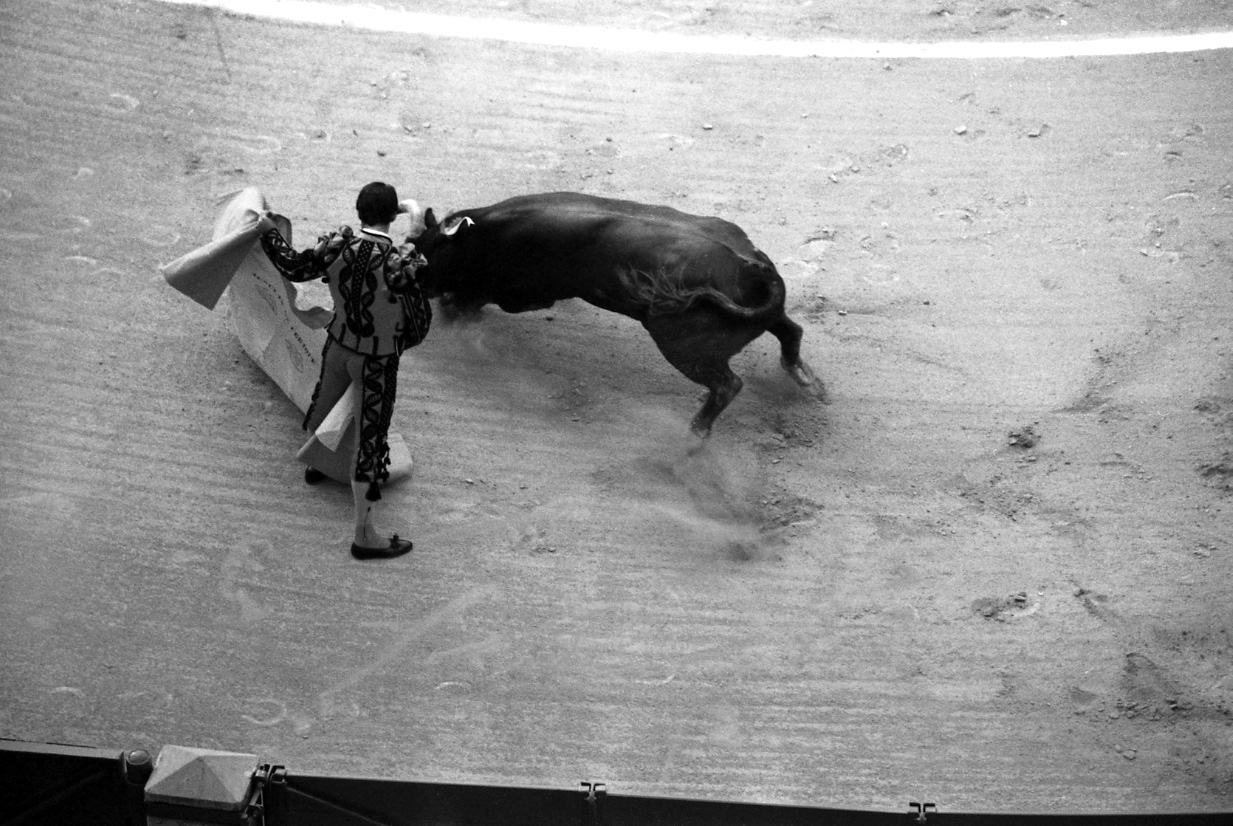

I will watch six bulls get massacred; there will be lots of blood. As the bullfight begins, I realize that I’m unable to watch except through the lens of my camera. After each bull is killed, one or two of their ears are chopped off and the carcass is dragged away by a team of mules. As they’re dragged away their tongues hang out, and with legs bouncing in the air, they leave a bloody trail in the dust of the arena. Then the matador parades around the arena, bowing and waving, and the crowd throws hats and flowers at him, while a team of men rake over the path the bull’s carcass has left.

By the time the third bull runs into the arena, the sun is a little lower in the sky, and I have become numb to the blood and death. I lean back in my chair and look around, as I think to myself what a shame it is that I brought only black-and-white film. I feel both horrified and more alive than I’ve ever felt. By now the other American students have gotten hungry and left to find sandwiches. I stay behind, hoping some meaning or explanation will reveal itself to me.

The Spaniards call this a “corrida,” which actually doesn’t translate to bullfight; a closer translation would be “the running.” And the event itself certainly seems more like a slaughter than a fight. In reality the bull doesn’t have much chance of avoiding death. The corrida is more like a ritualistic animal sacrifice, something that many cultures have engaged in at some point in their history. A chill runs down my spine, as I realize that the delicate balance between life and death is being played out in front of me like a broadway production—except the blood is real.

I begin to wonder what role the bullfight could have in Spain’s future. Surely there is no room in a modern European society for such a brutal display of death and tradition. Even now a majority of Spaniards disapprove of or have no interest in bullfighting. How long will it be before the entire tradition falls into obscurity, and will anyone miss it? I leave the stadium with my thoughts reeling, and at the same time feel a reflective, yet guilty, calm, which follows me for a long time afterward.

Further Reading:

John Hooper, The Spaniards: A Portrait of the New Spain, 2nd ed. (Penguin Books, 2006). Adrian Shubert, Death and Money in the Afternoon: A History of the Spanish Bullfight (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Eric Solsten and Sandra W. Meditz, editors. Spain: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1988, http://countrystudies.us/spain/.